How Kaiser Permanente turned Receptionists into Life-saving Heroes of the Hospital

LinkedIn, Shawn Achor

March 16, 2018

In December 2016, I was driven out in the middle of nowhere in Northern California on a cold, wet morning. Bewildered as to why we were venturing so far out from the city, I checked Google Maps more and more frequently as cows began replacing Starbucks. Then I lost cell service. Finally, the car stopped in front of what appeared to be an old mill. To my surprise, the inner building and grounds that had once served a much different capacity had been transformed into a venue for life-affirming events such as weddings and reunions. This stark makeover seemed symbolic of the reason I was there: to learn about a new program at Kaiser Permanente that had transformed receptionists and other support staff into lifesaving medical providers. As of our meeting, this program had saved 471 lives.

In the room generally reserved for brides and their entourage, I had the honor of meeting with Dr. Sanjay Marwaha and Monica Azevedo from the Permanente Medical Group, who told me about the program titled “I Saved a Life.” Its approach was as straightforward as it was innovative: to empower all hospital employees—even people without medical training—to provide medical care. I know what you’re thinking: “Here comes a malpractice suit.” But hear me out.

In a Small Potential organization, there are very clear mental compartments about who is capable of leading change. Stifled by layers of hierarchy, such organizations create a false dichotomy between those with the power to decide, innovate, or act and those who must blindly follow. In the case of the medical industry, it is too easy to conceive of doctors and nurses as “medical providers” and the administrators and receptionists as “support staff.” This seems, at first glance, like a perfectly logical way to go about delineating tasks in a hospital setting. But as we’ll see, this type of thinking limits our ability to tap into Big Potential.

Imagine you have an earache. You go to your primary doctor. After you wait half an hour in the examination room, he swoops in, takes a peek inside your ears, and then refers you to an ENT specialist. You make an appointment for your ears, fill out a bunch of paperwork about your ears, the doctor asks about your ears, and you pay the receptionist for your ear exam. All of this seems normal because you have a problem with your ears.

But what if your earache is actually caused by a virus that you caught because the anxiety that is keeping you up at night had weakened your immune system? After all, you are an inter- connected organism, and there are any number of other things happening in your brain and body at any given moment that could be causing you to experience pain in your ear. But because your ENT specializes in ears, she might not think to ask you about your mood or your sleep patterns, and fail to get at the root cause of the pain in your ear. In a world in which medical providers are becoming more and more specialized and siloed into smaller and smaller domains, the team at Kaiser wondered, how can we step back and see the bigger picture?

The answer they came up with was quite simple: They would upend the false dichotomy that governs most hospitals in the world, and empower those outside the traditional role of “medical provider” to address health issues that might slip through the cracks of a highly hierarchical organization. Knowing that one of the most effective, and yet underutilized, tools for improving health outcomes is preventive care, the team at Kaiser decided to invite and train receptionists to find ways to increase the number of patients who took advantage of preventive care options.

Now, if you called to book an appointment for any reason—even for an earache—the call center representative could first check to see if you are overdue for a preventive screening (mammogram, cervical, or colorectal) and then ask if you would like to book an appointment. The beauty of this program is that Kaiser empowered anyone who is involved in overseeing, providing, or scheduling care—medical degree or no medical degree—to contribute to the core objective of the organization: improving patients’ health.

And boy did it work. If a patient agrees to be booked for a screening and a life-threatening cancer is found in time to be treated, that is considered a life saved. When Kaiser Permanente tracked the outcomes, they found that of the 1,179 women who had been diagnosed with breast cancer in their hospitals since the new program began, a whopping 40 percent had booked that mammogram at the suggestion of one of the non-medical staff through the “I Saved a Life” program. One life saved would have made the program worthwhile. Four hundred and seventy-one lives saved is transformative.

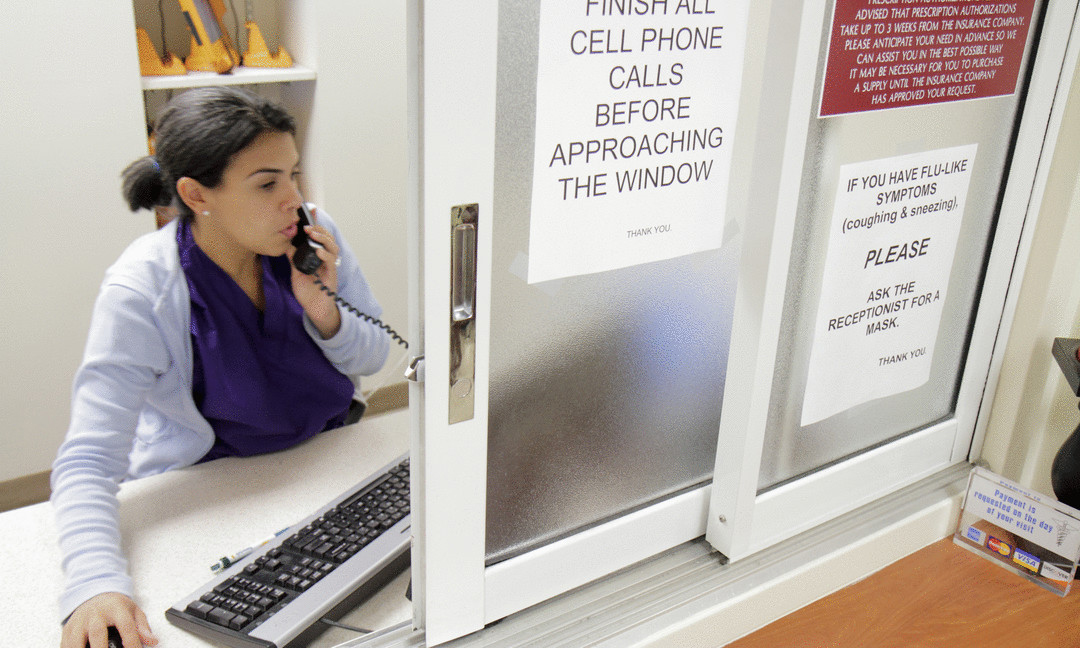

If I asked you which employees you would expect to be among the greatest heroes in the hospital, you probably wouldn’t think of receptionists—a group of people who don’t ever step foot in the operating room, who don’t take blood, read X-rays, or even see patients face-to-face. And these heroes are often sitting in a call center chair surrounded by cubicle walls, which means that in order to persuade a patient to come in for their screening, they have to rely on emotional connection, data, and storytelling, all over the phone. And to do this effectively first and foremost requires they believe that they have the power to make an impact: to be able to say “I saved a life.”

The ultimate key to the program’s success was that it allowed anyone to be a leader regardless of job title, college degree, or years of experience. In other words, they created a system where people could lead from every seat.

No matter what field you are in or what type of work you do, believing that you, too, can lead from any seat multiplies your potential to create change. People who try to be superstars alone, who believe that they have the power to create change only if and when they occupy an “official” leadership role, will achieve only Small Potential. But when everyone in a system, no matter their official role or position, shares the work of creating change, there is virtually no limit to what can be achieved. We need to free ourselves from the tyranny of labels if we are to achieve Big Potential.

So many people believe that leadership is an individual sport—a burden to be shouldered alone. Yet, trying to carry all the leadership responsibility alone is the quickest path to burnout. If you were running a hospital ward and you thought the outcome of each and every patient was on your shoulders alone, you might feel compassion fatigue. Similarly, if you were a sales manager or CFO who thought you had to bear the sole responsibility for your company’s returns to its shareholders, you’d be crushed by an enormous weight. If as a parent you felt like you had to make all the decisions about your teen’s future, you would be creating an undue, unnecessary, and unhelpful relationship stress. Think about how often high-potential leaders have been told, “If you want the job done right you have to do it yourself.” This is not only untrue, it’s the fastest way to put a cap on what you can achieve. Your time and energy are finite, but the demands on them are in nite. You simply cannot meet those demands unless you EXPAND responsibility and the work of leadership to everyone who has a stake in the mission.

If you believe that leadership and influence are limited resources given only to those at the very top, it shuts off the part of your brain that could be searching for new possibilities or opportunities to lead. This cognitive meltdown not only prevents you from seeing the ways in which you do have the power to create change, it dramatically lowers your energy, creativity, happiness, and ultimate effectiveness. If we want small potential we should leave leadership in the hands of the “leaders.” If we want Big Potential we must inspire and enable others to lead from every seat. When you let go of the idea that only certain people have the power to lead, you can dramatically amplify not only your own power but also the power of the group as a whole.